At a recent presentation, Apple introduced several new subscription services including magazine platform Apple News+, iOS and macOS gaming service Apple Arcade, and the Apple TV+ video service that the company...

At a recent presentation, Apple introduced several new subscription services including magazine platform Apple News+, iOS and macOS gaming service Apple Arcade, and the Apple TV+ video service that the company has promised to fill with unique movie and TV content from famous industry figures. In general, the presentation didn’t surprise me. Some of the features announced by Tim Cook and his colleagues have been available for some time already (like Apple Card), other long-awaited releases weren’t discussed in enough detail. Apple invited a lot of celebrities, including Steven Spielberg, Reese Witherspoon, J.J. Abrams and many others. The guests talked about their plans to create new shows and movies with the company.

Steven Spielberg will launch a reboot of Amazing Stories. Reese Witherspoon will join Jennifer Aniston in The Morning Show. Oprah Winfrey is already working on two documentaries on harassment and mental illness, and J.J. Abrams will film a show about a woman trying to make it big in the music industry. Another anticipated release is See, a show about a future where humans lose their sight and are forced to create new methods of interaction to survive. The public can expect a lot of new projects. But like I said before, not a lot of details are currently available. We should wait until the fall to learn more.

At first glance, there’s nothing unusual about yet another streaming platform. Except for the fact that the world’s largest corporation is finally presenting a platform that has been promised for a long time. I would have instantly forgotten about Apple TV+, at least until the first shows and movies were released, if it wasn’t for the startling news about the world’s last video rental store closing, part of the previously enormous Blockbuster network located in Morley, Australia. This final victory of online services over physical formats got me thinking not only about the evolution (or revolution) of content sharing technologies, but also about the transformation of our media consumption culture.

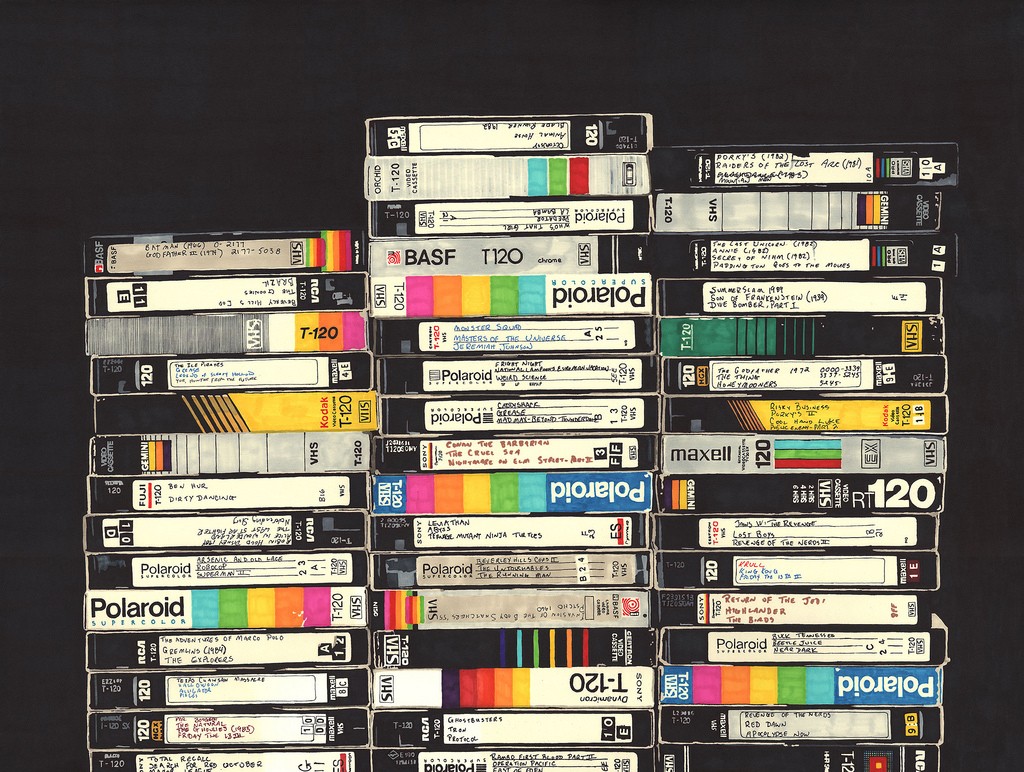

The VHS era

The culture of consumption or the consumption of culture — no matter how you put it, this is the top priority for producers, directors and other players involved in creating or releasing media projects. Regular users care about convenience and, whenever possible, affordability. They also care about getting a decent range of options to choose from.

Until the 1980s, people would watch movies in theaters. Then, the video rental era started. After a battle of formats — Betamax by Sony and VHS by JVC — the latter won. With the advent of affordable video players, watching movies became an at-home pastime, so movie theater owners were forced to improve their services by offering more cinema halls, food and drinks to continue attracting viewers.

During the era of ‘Movie theaters vs. VHS’ viewers had to choose between large screens with high-quality sound and a large range of options they could watch whenever they liked.

It’s worth noting that competition was often unfair, because offline piracy emerged with the widespread use of VHS. Production companies in countries lacking a structured content distribution policy especially suffered from the sales of unlicensed copies. Russia in the 1990s and early 2000s is a particularly striking example.

But the era of video rentals soon passed. Although VHS was replaced by more advanced mediums like DVD and Blu-Ray, these were no longer necessary for the mass viewer who had transitioned to the Internet.

That’s what made me so nostalgia after reading about the last Blockbuster video rental store. But naturally, this battle has its own modern continuation.

Movie theaters vs. the Internet

In the Netflix era, offline movie theaters continue to exist, but they are now competing against streaming platforms instead of discs and video tapes. The problem with piracy didn’t go away. If anything, it got worse as pirates made their way online. Now you can share a file without losing any of the quality just by sending it to another device online.

Technical progress has brought us to the point where all kinds of content can be delivered to users’ personal devices — from silly YouTube videos and glamorous Instagram photos to entertaining shows like Game of Thrones and intellectual films like Roma by Alfonso Cuaron, which was released in partnership with Netflix and received three Oscars.

The option of personalizing your watching experience, especially on small smartphone screens, partially transforms the viewers’ perception, but not the goal behind content consumption.

Disregarding festival and arthouse films, cinema has always been focused exclusively on entertainment. Sure, some films were effectively used as propaganda, but this propaganda was effective when presented in an interesting, captivating format, or at least as a supplement to the main attraction.

From the very first movie screenings, cinema was a collective activity, meaning that perception was influenced by the overall mood in the cinema hall. For example, when everyone is laughing at a character’s actions on the screen, most people will at least smile, even if they don’t completely get the joke.

When viewers got access to television, followed by VCRs, TV watching remained a communal activity: there was still just one screen. The conflict between a wife watching a melodrama and her husband who wants to switch channels to watch a football match is now seen as a caricature on family life, but it still represents a real fact of life.

And then came the Internet.

Sure, even today we can get together with friends and family to watch the third season of Twin Peaks. But if some people don’t like the show or David Lynch in general, they can go back to their room and watch something else on their smartphone/tablet/laptop.

That’s right, the Netflix model changed our approach to content consumption. Some users appreciate the new format, while others hate it. But the ones with the strongest opinions on this question are major production companies and TV channels that make money on movie screenings and live TV.

The classic monetization model for cinema involves the ready-made product being released in movie theaters, viewers paying for tickets, and half of the collected profits remaining with the movie theaters. If the box office is high enough for both the theater and the production company, the film pays off.

The classic TV monetization model features a channel creating shows, films and various programs, which are all paid off with commercial revenue. There are also some premium TV channels which operate on a subscription-based model.

The Netflix model is significantly different from the others. The company is thriving thanks to the low prices for on-demand online streaming of their own content. For a conservative sum, users gain access to the most popular and relevant content. Netflix has no interest in sharing their revenue with movie theaters. And yet this service has ambitions of participating in prestigious festivals like the Oscars, Venice Film Festival, Cannes. And if they have already managed to conquer Venice and the Oscars, the jury at Cannes is against the company and supportive of French movie theaters, demanding screenings at regular theaters.

Netflix notoriously solved this problem by renting out theaters for several weeks and taking all the revenue for themselves to meet this qualification point.

It looks like the question of artistic value is no longer relevant, or at least it has dropped from the top of the list of requirements. Today, it’s all a matter of competition between different industry players.

Corporations vs. corporations

Personally, I think that the Steven Spielberg can serve as an example to illustrate how the modern movie and TV production industry is changing.

Many were puzzled when Spielberg appeared at the Apple presentation, claiming that he will collaborate with the company’s new platform. How could it be: first he berates Netfix, only to join their competitor. Is Steven just a sellout?

But I think I can defend Spielberg against such claims. The director wasn’t criticizing the platform itself, but the fact that Netflix films were approved to participate in the Oscars.

Because Netflix is focused on showing their content on their own platform without sending films to movie theaters, Spielberg believes this is the same as television and that the company should either follow the rules and show its films in theaters, or participate in TV competitions like the Emmy Awards.

The simple conclusion that I’d like to draw is that there are no idealists in business, even in the arts. Especially when we’re talking about modern media content, which is a highly lucrative industry; so lucrative, in fact, that IT giants like Apple and Amazon are fighting to get a piece of the pie.

Share this with your friends!

Be the first to comment

Please log in to comment