Each major technological invention is commonly explained as the result of a scientific breakthrough, a fortunate coincidence, or the genius of a particular individual. Television, the computer, radio, artificial intelligence—all of these usually appear as products of their time, shaped by its level of knowledge, materials, and manufacturing capabilities. But a closer look reveals something else: almost no technology ever emerges “from scratch.”

First comes an image—vague, sometimes naïve, sometimes philosophical. Then a language emerges that allows this image to be described and discussed. And only later, years or even centuries afterward, do prototypes, engineering solutions, and mass-produced devices appear. In this sense, the history of technology is not a straight line of progress, but a long process of imagining the future.

Television Before Television: The Idea of “Seeing at a Distance” and the First Schemes

The prototype of television emerged long before the advent of electricity—as a human desire to see farther than one’s own eyes allow. In the nineteenth century, European culture was literally captivated by the idea of expanding the senses. Optics, photography, and projection devices were reshaping the very notion of reality, and the thought that an image could not only be captured but also transmitted over a distance gradually ceased to seem fantastical. This aspiration was fueled not only by science but also by everyday experience: the acceleration of life, the growth of cities, and the desire to witness events taking place beyond one’s immediate surroundings.

The first step from dream to engineering language came in the form of mechanical methods for “breaking” an image into parts. A key element here was the Nipkow disk—a device patented by Paul Nipkow in 1884 under the name “electric telescope.” It proposed a clear principle of line-by-line image scanning, an idea without which early television is simply impossible to imagine.

By the 1920s, working—albeit still primitive—systems began to appear. In 1926, John Logie Baird publicly demonstrated the transmission of moving images for the first time, and in 1927 Philo Farnsworth presented a fully electronic television system. It was at this moment that television ceased to be an experiment and became a technology with an obvious future.

The Computer Before the Computer: An Attempt to Turn Thinking into a System

The history of the computer most clearly shows that technological prototypes are often born not in laboratories but in philosophy. Long before the appearance of computing machines, thinkers were asking: if reasoning follows logic, can it be described using formal rules? Is it possible, figuratively speaking, to “package” thinking into a system? These questions arose in an era when neither suitable machines nor programming languages existed, yet there was already a sensed need for a more rigorous and universal way of working with knowledge. In this context, philosophy served as an intellectual testing ground for future technologies.

As early as the seventeenth century, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz wrote about the possibility of a universal logical calculus—a language of reasoning in which disputes could be resolved not through emotion but through calculation. He was interested not in the mechanization of arithmetic, but in a far bolder idea: making the process of thinking transparent and formalizable.

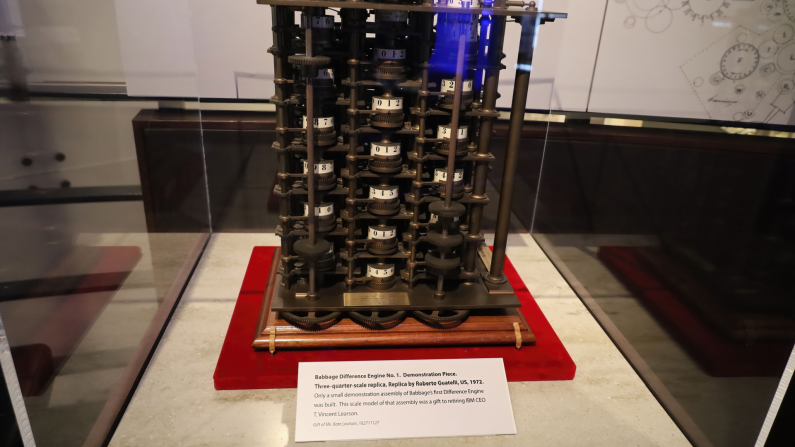

In the nineteenth century, this philosophical line took on a mechanical form. Charles Babbage designed the Analytical Engine—a device whose logic is strikingly similar to that of a modern computer. His project already incorporated programmability, memory, and operational control. The source of inspiration was the Jacquard loom, where the pattern of the fabric was determined by punched cards. It was here that the idea of a program as an instruction independent of the performer first became clearly articulated. Although the Analytical Engine was never built, its concept proved extraordinarily resilient. Nearly a century later, it was “rediscovered” in electronic computing machines, confirming that a prototype can outlive its own era.

Radio Before Radio: How Scientific Theory Became a Voice from the Air

If television began with visual imagination and the computer with logical abstractions, radio grew out of the dream of communication without a physical carrier. Until the end of the nineteenth century, the very idea of transmitting information “through the air” seemed almost mystical. Yet it was science that gave this idea a strict foundation. Interestingly, the concept of wireless communication for a long time was perceived as something bordering between science and illusion. This made early experiments especially impressive to contemporaries, while at the same time, in the public eye, aligning them with mysticism and occult practices.

The decisive moment was James Clerk Maxwell’s theory of the electromagnetic field, formulated in the 1860s. It predicted the existence of electromagnetic waves—invisible yet real. A few decades later, Heinrich Hertz experimentally confirmed their existence, demonstrating that such waves could not only be detected but also controlled.

Wireless communication acquired practical form in the work of Guglielmo Marconi. In the 1890s, he created the first systems of radiotelegraphy, and in 1901 transmitted a signal across the Atlantic Ocean. Radio quickly ceased to be merely an engineering achievement: it radically changed the sense of distance and presence. A voice coming “from nowhere” became part of everyday life.

Artificial Intelligence Before AI: From a Philosophical Question to a Scientific Program

Today, artificial intelligence is associated with algorithms, neural networks, and computational power, but its prototype is an old human question about the nature of mind. Is it possible to create thinking outside the human body? Where does the boundary lie between mechanism and consciousness?

A turning point was Alan Turing’s paper “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” (1950), in which he proposed discussing intelligence not through definitions but through behavior. The question “Can machines think?” was replaced by a more practical one: can a machine’s answers be distinguished from those of a human? This marked a step from philosophical reflection to a testable model.

And in 1956, at the Dartmouth Summer Research Project, the term “artificial intelligence” was officially introduced as the name of a research field. At the same time, Norbert Wiener’s cybernetics was developing, offering a language of feedback, control, and self-regulation. It was here that AI began to take shape not as a metaphor, but as a discipline. From that moment on, the discussion of artificial mind became part of the scientific community, with its own methods, expectations, and limitations. The idea acquired an institutional form.

Across all these histories, one pattern can be traced: technology is almost never the first step. First comes a desire—to see, to calculate, to communicate, to think differently. Then comes a way to speak about this desire, to discuss it, to argue about it. And only then does engineering turn the idea into a working mechanism.

Prototypes always emerge at the intersection of disciplines. Philosophy influences the architecture of computation, looms influence programming, physical theories influence modes of communication. A prototype is not an early version of a device, but an early version of the meaning the device is meant to embody. This is precisely why many technological ideas linger “in the air” for a long time, waiting for the right level of scientific and social development—until, finally, their time arrives.

Share this with your friends!

Be the first to comment

Please log in to comment