In today's rapidly changing world, even the seemingly conservative food industry is undergoing a profound transformation.

It has now become a high-tech niche akin to medicine and IT, where bioreactors and 3D printers compete with traditional farms, and the key players are not agri-holdings but biotech startups like Upside Foods and Perfect Day. Their goal is not to create yet another plant-based substitute but to revolutionize the very principles of food production: to grow meat from a few cells, to synthesize milk protein using programmed microbes, and much more. By 2030, these technologies promise to create a new market—and change what we understand by the word "natural."

How It Works: From Cell to Finished Dish

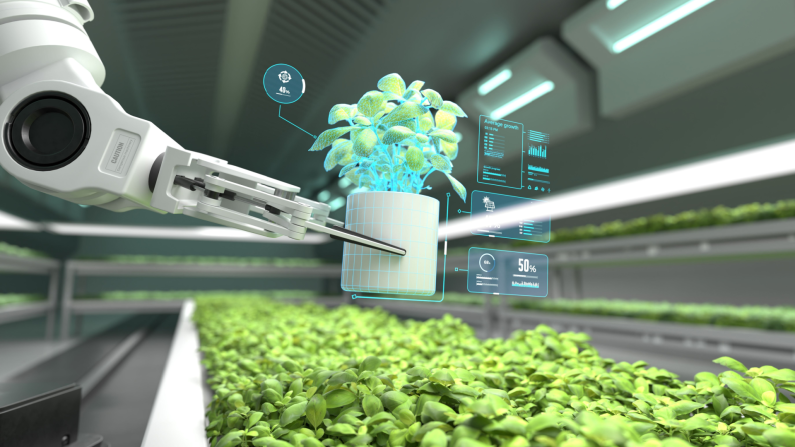

Modern food technologies are developing along three main tracks:

- Cellular Agriculture (Cultivated Meat)

This is not a plant-based analogue but real meat grown from a few animal cells. The process begins with a biopsy—taking stem cells from a cow, pig, or chicken. These cells are placed into a bioreactor—a sterile vessel.

Inside the bioreactor, an ideal environment is created, mimicking the animal's organism: a nutrient medium (a mixture of amino acids, sugars, and vitamins), controlled temperature, and oxygen levels. The cells divide and differentiate, forming muscle fibers—the basis of meat. To achieve the complex structure of a steak rather than ground meat, edible scaffolds are used, on which the cells "anchor" and grow in a predetermined direction.

The pioneer here is the company Eat Just, whose cultivated chicken nuggets have already been approved for sale in Singapore. The American startup Upside Foods (formerly known as Memphis Meats) is also building the world's largest factory for producing cultivated meat. Their key argument: producing such meat requires 96% less water and 99% less land, while reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 96%.

- Precision Fermentation

This technology does not grow cells but uses microorganisms themselves as factories. Scientists take ordinary yeast or fungi and, using genetic editing, "teach" them to produce the desired proteins.

A prime example is the company Perfect Day. Researchers introduced a gene responsible for producing milk protein (casein and whey) into microscopic fungi. The fungi are fermented in sugar-based bioreactors, producing exact copies of animal proteins in the process. These proteins are then purified and used to produce milk, ice cream, cheese, and yogurt that are molecularly identical to their bovine counterparts, but without a single animal.

The California-based startup The Every Company operates similarly, producing egg white. Their technology allows for the creation of egg products for baking, mayonnaise, and even meringue, without using poultry farms.

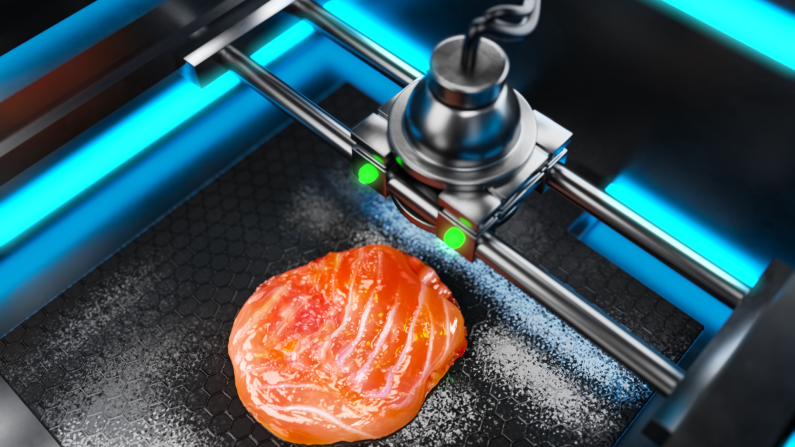

- 3D Food Printing

This is an innovative method of food preparation and giving dishes complex shapes. Food 3D printers operate on the principle of layer-by-layer deposition, using "inks"—special pastes based on vegetable, fish, or meat purees, dough, chocolate, or even protein masses from cultivated meat.

The key advantage is personalization. For instance, the Israeli company MeaTech 3D (now Steakholder Foods) prints complex marbled structures for steaks by alternating "inks" from muscle and fat cells. The Spanish project Novameat is developing a printer capable of recreating the microfibrillar texture of muscle fibers for plant-based steaks, making them "juicy" and convincingly similar to meat.

But it's not just meat products that are printed. Confectionery startups use the technology to create chocolate figures of incredible complexity, and in the field of nutrition for the elderly, easily consumable dishes are printed from purees.

Taste Transformation: 'Synthetic' is No Worse Than 'Original'

The advantages of this new type of food extend far beyond ethics and ecology.

-

Composition Control at the Molecular Level. Technologies enable the elimination of harmful components that harm health while adding beneficial ones. For example, in cultivated meat, the ratio of saturated to unsaturated fats can be controlled, reducing harmful cholesterol. In fermentation products, lactose or allergens can be completely eliminated.

-

Safety and Purity. Production in sterile bioreactors reduces the risk of contamination by pathogens such as Salmonella and E. coli to zero and eliminates the need for antibiotics, which are used extensively in traditional livestock farming.

-

Environmental Efficiency. Producing protein through precision fermentation requires tens of times less land and water than conventional farming. The company Air Protein has gone even further, creating protein flour from microorganisms that feed on carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and minerals. This turns a greenhouse gas into raw material for food production.

-

Flavor Design. For example, one can "construct" meat with a more intense taste or design a fruit with an unusual combination of aromas that does not exist in nature.

Who is Cooking the Future Meal

With the industry's transformation, a new labor market is emerging where biology meets design and engineering.

-

Food Engineer-Designer. This is a specialist who creates not only the taste and composition but also the texture and appearance of a product. They work with 3D models to design how a steak will look in cross-section, and how fat layers will be distributed. They select ingredients so that a plant-based burger not only mimics the taste of meat but also "bleeds" beetroot juice and has the right crunch and mouthfeel.

-

Bioprocess Engineer. A key figure in production. They optimize the operation of bioreactors: control the parameters of the nutrient medium, temperature, pH, and agitation to maximize product yield and reduce cost. This is precisely the person who turns a laboratory experiment into a scalable industrial process.

-

Cell Line Specialist. If a breeder once worked with whole animals, they now work with their cells. Their task is to select and maintain cell lines with the best properties: they divide quickly, are stable, and form ideal muscle or fat tissue.

-

Food "Ink" Architect.

Developing formulations for 3D printing is an extremely complex task. The "inks" must be liquid enough to pass through the printer nozzle and viscous enough to hold their shape after printing. Such a specialist works with hydrocolloids (agar, alginate), proteins, and fibers to create edible pastes with specified properties. -

Ethical and Regulatory Manager. After all, new products face consumer skepticism and strict regulatory requirements (the FDA in the USA, EFSA in Europe). This specialist builds public dialogue, prepares dossiers for approvals, and develops transparent labeling.

Industry Challenges and Risks

Despite progress, the path to a mass market is fraught with serious difficulties. The key ones are:

-

Economics of Scale. Today, producing one cultivated burger can cost tens, if not hundreds, of dollars. The main expense item is the costly nutrient medium for the cells (often based on fetal bovine serum, which contradicts ethics). Although startups like Mosa Meat and Aleph Farms are actively working to replace it with plant-based analogues, the challenge of reducing costs to price parity with premium meat (approximately $10-15 per kg) remains key. Without this, the products will remain niche items for affluent, eco-conscious consumers.

-

Regulatory Maze. Each new product requires a lengthy and expensive approval process. Following Singapore, only a few countries, including the USA (where the FDA gave the "green light" to products from Upside Foods and Eat Just), have taken the first steps. In Europe, the EFSA process is extremely conservative and can take years. Inconsistency in international norms hinders global expansion.

-

Consumer Perception. Fear of GMOs (although they are often present in precision fermentation technologies) and general distrust of "synthetic" products are serious barriers. Success will depend on transparency, education, and honest communication about the real benefits for health and ecology.

-

Infrastructure Gap. The transition from a laboratory prototype to mass production requires the construction of completely new types of plants—bioproduction facilities (fermentation farms), not slaughterhouses. These are colossal capital investments that slow down growth.

To date, there are already over a hundred startups in the alternative protein field worldwide, with the lion's share concentrated in the USA, Israel, and Europe. Most likely, by 2030, we will see not the complete displacement of traditional agriculture, but the formation of a hybrid food system. Cultivated meat and fermentation proteins will occupy the premium segment and become a key ingredient in processed products (sausages, pastes). 3D printing will find a stable niche in personalized nutrition (for hospital patients and athletes) and the confectionery arts.

Thus, the path leads not to a gastronomic utopia but to a smarter, more diversified, and technologically advanced industry capable of solving specific problems: reducing the burden on the climate, freeing up land, and offering new, composition-controlled products. The main question for the next five years is not "is it possible," but "how quickly can it be made accessible?" And the answer will be given not only by scientists in laboratories but also by engineers at the bioplants under construction, regulators in agencies, and, ultimately, ordinary consumers at the counters.

Share this with your friends!

Be the first to comment

Please log in to comment