Imagine a picture of the ideal future. Smart and beautiful people develop ever more perfect cars and they live in large, bright houses. They are free from disease and addictions, they avoid conflict, are protected, and happy with everything.

There is only one small detail: in the corner of this picture there is a small inscription "Made in China", and all of these people of the future are Chinese.

And this is not the result of a lack of imagination - there is some reason to imagine the future this way.

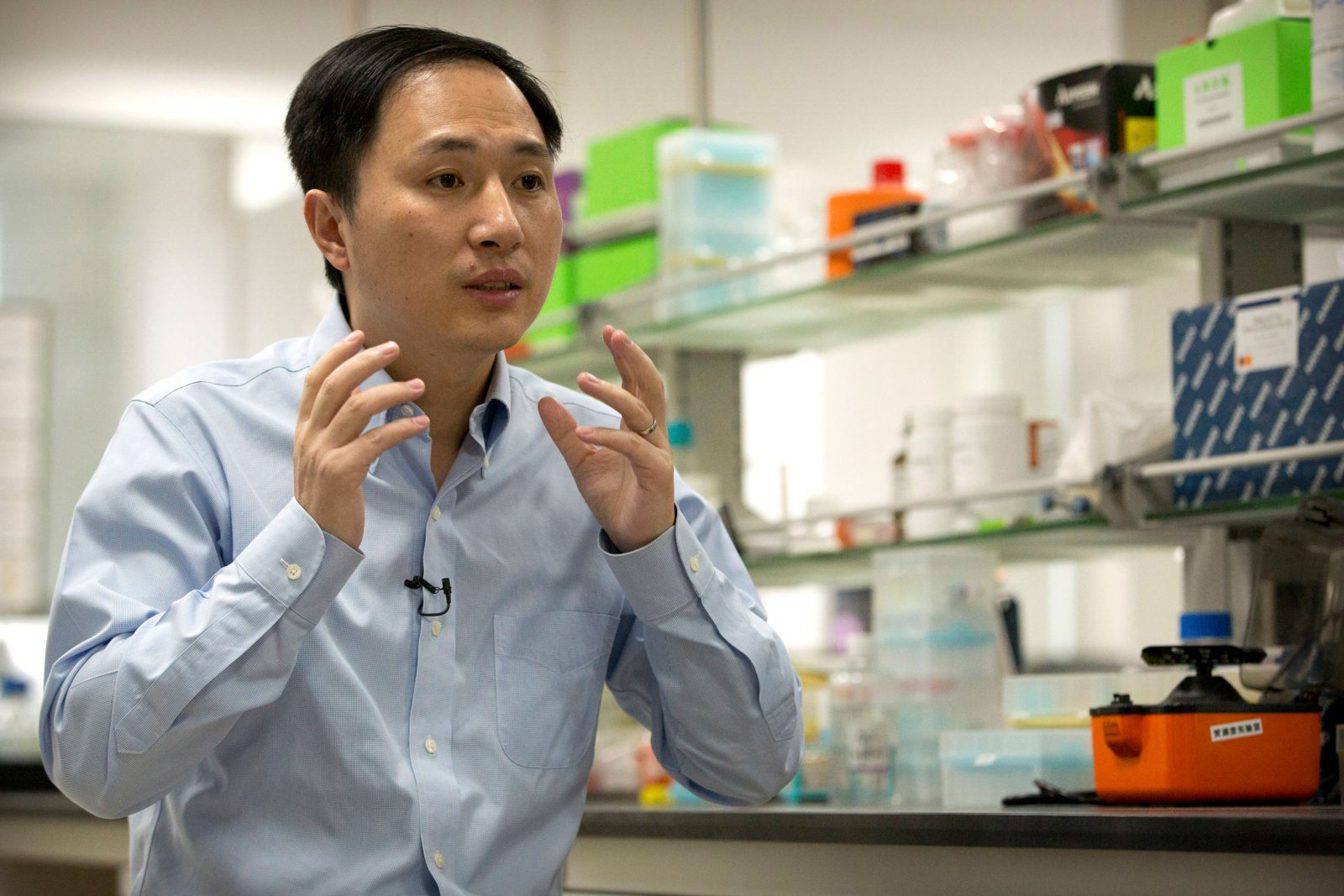

On November 25th, 2018, big news from China spread around the world. It turns out that twin sisters with an edited genome had recently been born in the Celestial Empire. The head of the experiment, scientist He Jiankui from the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, proudly announced this development.

He said that the twins, Nana and Lulu, had a chance to become immune to HIV infection. In the embryonic stage, their genome was changed using CRISPR technology, also called molecular scissors. Without going into too much detail, it allows you to insert the desired gene at a specific place in the overall chain. The DNA will then be altered and will probably be inherited by descendants in the future.

At first glance, this is great news; everyone should hug and celebrate. But this is not the case. The scientific community is outraged. Scientists from different countries have called the experiment illegal and futile. Jiankui's compatriots have even said that it discredits Chinese science. Let's try to figure out what's going on here.

The scientific world accuses He of violating professional ethics. And it looks like there is every reason to believe this. This gene intervention can have far-reaching consequences. For example, unwanted mutations can not only do damage to the body, but also have an unpredictable effect on future generations. The International Code of Medical Ethics clearly states that all research involving humans must have a sound scientific basis. And the decision on the expediency of the experiments is made by an independent ethical commission.

The State Health Committee of the People's Republic of China claims that he did not receive an application for the experiment. And furthermore, he did not convene a special commission. The permission to do the research is thought to be fake. As a result, He Jiankui has been on unpaid leave since February of 2018 and no one expects him to return to the laboratories of his native university in Shenzhen until January of 2021. And neither the management of the university or the administration knows anything about any experiments.

It is difficult to verify whether the Chinese health officials are cunning, fearing a scandal, or really did not give permission for the study. However, if the authors of the study went the official way and applied for the experiment, they most likely would have been refused.

Genome editing can be considered when all other options have already been exhausted, without having the desired effect. But the human immunodeficiency virus is well studied. Methods of protection against it are known, and the course and development of the disease can be controlled. Further, the CRISPR method, although the most advanced today, has shown in a number of experiments that it does not always give perfect results. According to scientists from the Sanger Institute, the technology is still too invasive for the genome.

And finally, the altered gene not only increases the girls' risk of infection by other viral diseases, but also from dying from the flu, said Dr. Kiran Musunuru from Pennsylvania State University. So, as you can see, there are plenty of reasons for rejecting the study.

Another oddity of this story is that He Jiankui did not provide the scientific community with independent confirmation of the results of his research. Instead, He was interviewed by the Associated Press and posted a series of staged videos on YouTube about his work. Details of its design have not been published in a journal and have not been verified by other scientists. He also cannot show the girls to the public; the parents want to remain anonymous. This begs the question: was there an experiment at all?

Jiankui couldn't help but be aware of the need to provide information about the study. He is not an amateur scientist. He studied at Rice University, where he also earned his doctorate and he has also worked at Stanford. He returned to his homeland under the Thousand Talents program and received a government grant - about $6 million - for a DNA sequencing project.

By the way, this may shed light on the source of funding for the experiment since Jiankui did not receive official permission or any state money for the research. But any grant involves reporting, and the activities of a geneticist could hardly have gone unnoticed to officials in China.

When it comes to the timing of the release, it was perfect: the day before the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing in Hong Kong. Coincidences do happen. He could have discussed the need, conditions, and ethical aspects of the genetic intervention. Of course, Jiankui held a conference at the summit, but he answered questions evasively or remained silent. Now there is no one to ask these questions - in early December, the media reported on the disappearance of the scientist: no one knows where he is and no one can get in touch with him.

It would be useful to remind you that this is not the first time the world scientific community has expressed concerns to China in the field of genetic engineering. The first high-profile scandal was in April of 2015. At the time, scientists from the University of Guangzhou tried to edit the genetic data of embryos for cancer treatment. The experiment was not entirely successful, therefore it is not particularly remembered. But the Chinese did not promise to stop.

The fact remains that there is no legal prohibition on changing human genes in China. But they do have the necessary technologies and developments, and the population does not oppose genome editing, as is the case in Europe or the United States. In China, of course, they support international initiatives (especially when everyone is watching), but they do it in their own way.

One gets the impression that with the help of He Jiankui's loud statement, China was checking the temperature: to what extent is the advanced scientific community ready to move from discussions of changing the human genome to doing experiments. The answer is obvious: they are not ready. China is quite possibly the opposite. And so fantasies about the future being made in China are not so far from reality.

Share this with your friends!

Be the first to comment

Please log in to comment